The Hermenia, written by Dionysios of Mount Athos, provides detailed instructions for painting religious scenes. For example, it includes guidance on how to paint the Nativity, showing Mary kneeling and Joseph adoring the child. It also explains how to paint the Resurrection of Christ, particularly in the “Western type” style. Another important section covers the Apocalypse of the Church, with clear instructions on how to depict angels, saints, and symbolic scenes. These instructions were not only practical guidelines for artists but also a way to preserve religious meaning and tradition while allowing some flexibility in style Influence of Western Painting on Post-Byzantine Icons.

Orthodox Theology and Artistic Influence

During the Ottoman period (1453-1821), Orthodox theology played an important role in shaping icon painting. Greek Orthodox thinkers faced pressure from Western European ideas, especially from the Enlightenment. Many debates arose about how to balance Orthodox traditions with new influences. Scholars like G. Podskalsky explain that Orthodox clergy and monks often had limited formal education. Some groups were even resistant to learning, which affected how religious knowledge was shared. This context influenced the content and style of icons, as artists worked within both a religious framework and the cultural challenges of their time.

Italian Influence and Artistic Motifs

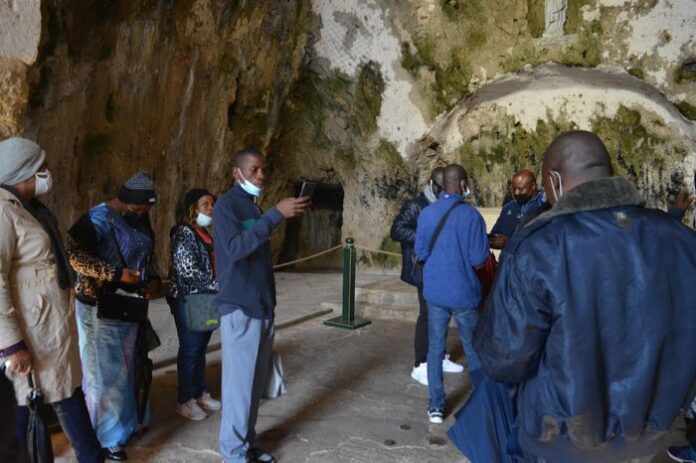

Cretan painters and other post-Byzantine artists often incorporated elements from Italian painting into their work. Studies by A. Sucrow and H. Deliyanni-Doris show how artists used motifs from Italian Renaissance art, adapting them to Orthodox themes. For example, the use of perspective, realistic figures, and architectural elements came from Italian examples but were combined with Byzantine iconography. This blending of styles created unique works that were both traditional and modern for their time Tour Guide Ephesus.

Patrons and the Role of Local Communities

In the post-Byzantine period, the system of patronage changed. Aristocratic and noble patrons were no longer the main supporters of art. Instead, village parishioners, local priests, and small communities often sponsored the creation of icons and frescoes. S. Petkovic emphasizes that these local groups became the new commissioning force. Their involvement ensured that art remained closely connected to religious practice and community life. This also encouraged the production of works that reflected local tastes and traditions, while still following broader Orthodox and Byzantine principles.

Post-Byzantine Artistic Trends

Overall, these factors—manuals like Hermenia, Orthodox theology, Italian artistic influence, and community patronage—shaped post-Byzantine icon painting. Artists maintained traditional Byzantine iconography while introducing stylistic innovations. They balanced religious content with evolving visual techniques, producing works that were deeply meaningful to their communities. The result is a rich and diverse tradition of icons that survived across Greece, the Aegean, and Anatolia, reflecting both continuity with the past and adaptation to new cultural conditions.